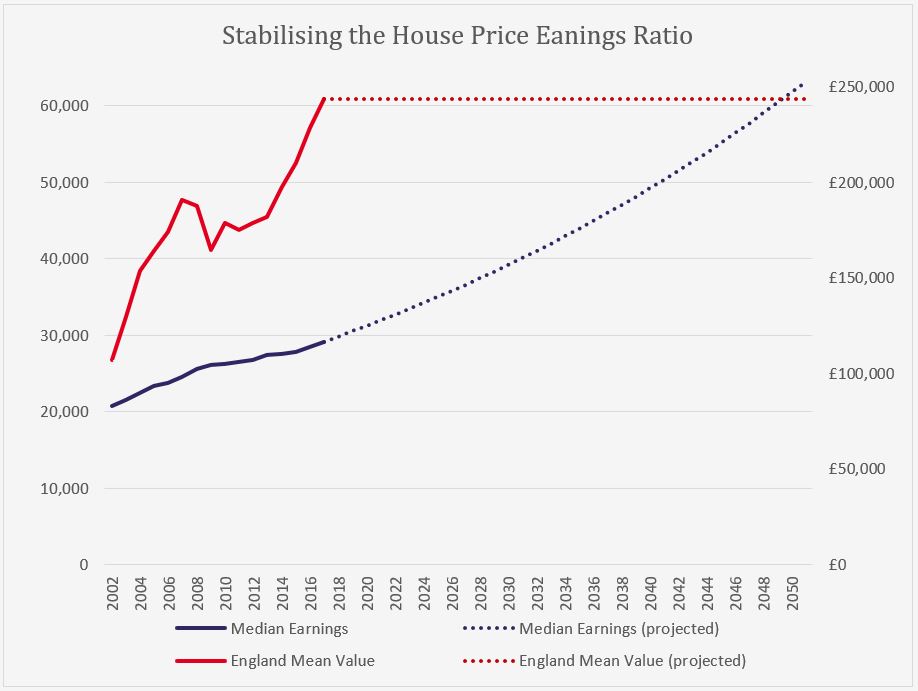

Clearly, at no point since 2002 has the English housing market been affordable (on this measure). The last time that was the case was just two years previously.

However, the point to note is this. Even if house prices stabilised tomorrow and neither fell nor rose at all, it would take more than 30 years for the affordability of the British housing market to return to the conditions that were prevalent in the year 2000. Even in this best case scenario, the British housing market crisis – which has already lasted around fifteen years – is only around a third of the way through. On this evidence, housing is a longer-term goal than decarbonising the entire economy in order to prevent catastrophic climate change. At least one, and possibly two more generations will have their standard of living curtailed by the housing crisis. That cannot be acceptable.

Absent a major intervention, the housing market will not fix itself. However, the nature of the housing crisis – prices that are too high relative to earnings – suggests the nature of the intervention required. In order to meet the needs of those priced out, we need to create an entirely new housing market for a new housing product whose costs are affordable relative to incomes. Moreover, when considering what type of discounts we should offer on housing, we should not link them to a percentage of the open market price because, when the open market for housing does reach a sustainable level, the value of the affordable homes we now propose to build will be discounted relative to that more affordable market – in effect, today’s affordable homes will end up blighted in tomorrow’s sustainable housing market.

The correct way to discount homes is to peg them to a sustainable relationship to incomes.

Notice that this will have two effects, the homes will certainly be affordable but they will also rise in value over time in smooth and predictable way. Look again at the graph above. Incomes rise far more smoothly than house prices. Even in the past ten years – which has seen an almost unprecedented squeeze on earnings – but nominal incomes have still risen.

The immediate salience of this is that it shelters Social Owners from one of the most notorious risks in the housing market, negative equity. In the medium term the possibility that your home will be worth less than the value of your mortgage is virtually nil. But it also has the more important effect of breaking the “ratchet” described above.

When the value of homes can go down as well as up, developers stand to go bankrupt if prices begin to fall but, if the value of these discounted homes will rise smoothly in line with earnings, then they are a good buy in all housing market conditions. Indeed, the demand for Social Ownership is actually likely to rise in a falling market or flat housing market because buyers will see it as a safe haven from the risk of the open market. Lenders too, may see the product as less risky and offer cheaper mortgages to social owners.

And, if the demand for Social Ownership exists in all market conditions, then it presents far lower risks to developers because they know that there will be buyers literally queued up to buy at known prices, even before they finish construction. The risks around the absorption rate disappear – the incentive is now to build out planning permissions as quickly as possible, rather than eke out sales at a rate the market will accept.

The first two of the three linked crises in the housing market dictate the nature of the solution that will resolve them. The third is perhaps less obvious. We have asserted that, alongside the crises of affordability and supply there is a crisis of design quality. We assert that there is comparatively little competition between developers on quality except at the very top end of the market. That should come as no surprise. When essentials are in short supply, we expect standards to suffer. In times of hunger, we expect growers to concentrate of yields and consumers to be less picky. Conversely, during the massive home building programmes that accompanied the expansion of the railways, developers competed fiercely on quality. That the stock of Victorian and interwar homes remains popular today is testament to the power of this competition.

At present, with house prices high and opportunities to build scarce, developers are incentivised to compete not on quality for the consumers but on cost – the lower their build costs, the more they can afford to pay for land – crowding out competitors. This dynamic was illuminated in some detail in the report Building the Homes We Need published by KPMG and Shelter in 2015. As they put it, “In a healthy market, competition will drive a better deal for consumers. But in house building, competition occurs at the wrong stage. The rational business strategy to manage land market risks is to minimise build costs and maximise sale prices by releasing homes slowly.”

We therefore propose to provide different incentives for the builders of Social Ownership homes. The price developers will receive for the homes is capped and the price they will pay for the land will also be fixed. Land and planning consent will go to the bidder whose proposal wins a design competition. The budget available for construction will be limited and margins tight but developers will need to balance their margin against the need to win the competition – which they can do only by offering the most desirable solution.

Too often over recent years, there have been calls to “solve” the housing crisis by encouraging people to accept less: smaller homes and less imaginative designs. There is no reason for this to be the case. Indeed, we argue that a drive to create accessible and desirable homes at the bottom end of the housing market, changes the incentives for the entire industry.

If potential buyers can opt either to buy a good quality Social Ownership home for £165,000 or to save up for an open market home at £240,000, developers of the more expensive homes will have to demonstrate that they provide additional benefits: more space, better environmental standards, higher ceilings, bigger windows, more character. The achievement of these improved specifications will increase costs – which will put downward pressure on land values.

National PLCs, with their immense economies of scale and purchasing power, will still hold considerable cost advantages – but pressure to turn show the value for money to the customer will put those advantages at the service of home buyers rather than land owners.